From the Austrian doctor and Freudian psychoanalyst, Wilhelm Reich, his 1946 essay Listen, Little Man! addresses a polemical question to the most common type of person. “Don’t you see that you’re a type, that there are millions of your kind and that you are destroying the world?” (page 107) When the ordinary and the meek sacrifice dignity to satisfy or even replicate some embarrassing oppressor, Reich provides the diagnosis for a treatable sickness.

“You’re sick, little man, very sick. It’s not your fault; but it’s your responsibility to get well. You’d have shaken off your oppressors long ago if you hadn’t countenanced oppression and often given it your direct support. No police force in the world would have had the power to crush you if you had an ounce of self-respect in your daily life, if you were aware, really aware, that without you life could not go on for one hour.” (16)

The little man represents the masses of ordinary people who move history, while remaining unaware of their own importance. In the meekness of the masses, Reich detects precisely what passes for normal in a repressive society ruled by the little man.

“I know, little man, you’re very quick to diagnose madness when a truth doesn’t suit you. You regard yourself as “normal”! You’ve locked up the lunatics and the world is run by you normal people. Then who’s to blame for all the trouble?” (86)

In his highly personal polemic against his public detractors, Reich evidently indicts the masses in German society where the twentieth century’s mass movements had their most fateful results. If he succeeds, Reich warns against the same events in recent history, and in the present, when your worst traits lead to destruction. When you seem impressed by the worst of everything, Reich mourns the wasted efforts of better men who have tried to teach you the truth about yourself.

“For centuries great, brave, lonely men have been telling you what to do. Time and time again you have corrupted, diminished, and demolished their teachings; time and time again you have been captivated by their weakest points, taken not the great truth but some trifling error as your guiding principle. This, little man, is what you have done with Christianity, with the doctrine of the sovereign people, with socialism, with everything you touch.” (64)

For any doctrine, whether religious or secular, socialist or individualist, the conventional conclusions seem scarcely distinct. The little man only remembers the worst parts of history, and repeats them, while forgetting the widespread wisdom from a recent past. “A great and wise man worked all his life trying to teach you,” referring to Karl Marx, “that you must free your society from all tyranny.”

“And you, little man, what did you do with the great man’s intellectual wealth? He gave you lofty, far reaching ideas, but you retained only one resounding word: dictatorship! Of all the super abundance of a great warm heart, only one word remained: dictatorship!” (38)

Even when you call a dictator proletarian, you invoke Marxism, but only in name. You still think like the little man, when “your thoughts pass the beautiful by and come to rest on the ugly!” (108) A chance at dictatorship easily impresses the little man, while any chance at healing seems ambiguous. Reich begins to regret his naïve optimism, from when he still hoped to raise awareness in an ordinary way, to save the little man.

“The little man in me wanted to win you over, to “save” you […] The less you understand, the greater your awe. You know Hitler better than Nietzsche, Napoleon better than Pestalozzi. A king means more to you than Sigmund Freud. The little man in me aspires to win you over, as you are ordinarily won over, with the tom-tom of leadership. I’m afraid of you when the little man in me dreams of “leading you to freedom.” You might discover yourself in me and me in yourself, take fright, and murder yourself in me.” (11)

The overwhelming animosity contained in a polemical book like Listen, Little Man! settles on an inner source for social misery as fatefully universal (in the Freudian sense), but not something inevitable. After expressing his deepest pessimism, Reich admits his most sincere hope. “You are great, little man, when you’re not mean and small.” (123) Reich believes you can still be great sometimes, “when you let yourself be guided by the thoughts of great sages and no longer the crimes of great warriors” (120). Without any great strength of his own, the little man idolizes not only “strength and greatness,” but more specifically,

“someone else’s strength and greatness. He’s proud of his great generals but not of himself. He admires an idea he has not had, not one he has had.” (7)

Despite his disappointment, Reich has high expectations because you are capable of great emancipations, even under the condition of conspicuous and universal impotence. “Only you yourself can be your liberator!” (8) You seem so much more alive and healthy when you are “free rather than cowed, candid rather than scheming; capable of loving, not like a thief in the night but in broad daylight.” (6) As a free-love type of Freudian, Reich dreams of treating the masses of the little man in a psychoanalytic session. The same manner his patients dwell on the therapist’s couch, the entire world seems to fill his office, desperately seeking his help, and asking him what to do differently. In his style, Reich answers with paradoxically simple advice.

“Nothing new or unusual. Just go on doing what you’re already doing: till your field, wield your hammer, examine your patient, take your children out playing or to school, right articles about the events of the day, investigate the secrets of nature. You’re already doing all these things, but you think they’re unimportant and that only what Marshal Medalchest or Prince Blowhard says or does is important.” (116)

The world’s truer majority of peasants, workers, scientists, and parents are far more important than the louder opinions of Maniacal Musk or Blowhard Bezos. Constantly advertising an unattainable future, you few who flaunt your riches prove each day your unfitness to rule. When you say you want to run the country like a business, you mean like your private company, like a dictatorship. You neo-monarchist CEOs deserve insults, rather than such widespread attention. “You’re a fart and you think you smell like violets.” (77) Reich has choice words for those who hide behind “freedom of speech” as a shallow justification for racist mockery and fascist ideology.

“You have mistaken the right of free speech and criticism for the right to shoot off your mouth and crack stupid jokes. You want to criticize but not to be criticized, and as a result you get torn to pieces and shot. You want to attack without exposing yourself to attack. That’s why you always shoot from ambush.” (76)

Everything seems like a joke to Elon Musk because his ironic salute is his only defense from doubt. Irony as a device has a time and a place, but irony’s ideological effect dissipates doubt. In an altogether confusing situation, even nonbelievers admire the piety of others. By specifically pretending to believe, not even the most devoted fanatic really trusts in such outwardly hollow promises. From a leadership without personality, the widest mass appeal safely depends on the most vague promise, and the most dim notion of freedom without individuality.

“They promise you not individual but national freedom. They say nothing of self-respect but tell you to respect the state. They promise you not personal greatness but national greatness.” (14)

In place of any genuinely personal individualism, you espouse its more abstract rhetoric against actual individuals. You idolize state power as an end for its own sake, rather than law as a means for bettering individuals. You never stop talking, yet somehow you never say anything new, so thinly disguised behind pathetic copies of twentieth-century fascism.

“That’s the kind of rubbish you talk, little man. And with such rubbish you set up armed gangs that kill ten million people for being Jews, though you can’t even tell me what a Jew is. That’s why you’re laughed at, why anybody with anything serious to do steers clear of you. That’s why you’re up to your neck in muck. It makes you feel superior to call someone a Jew. It makes you feel superior because you feel inferior. You feel inferior because you yourself are exactly what you want to kill off in the people you call Jews. That’s just a sampling of the truth about you, little man.” (31)

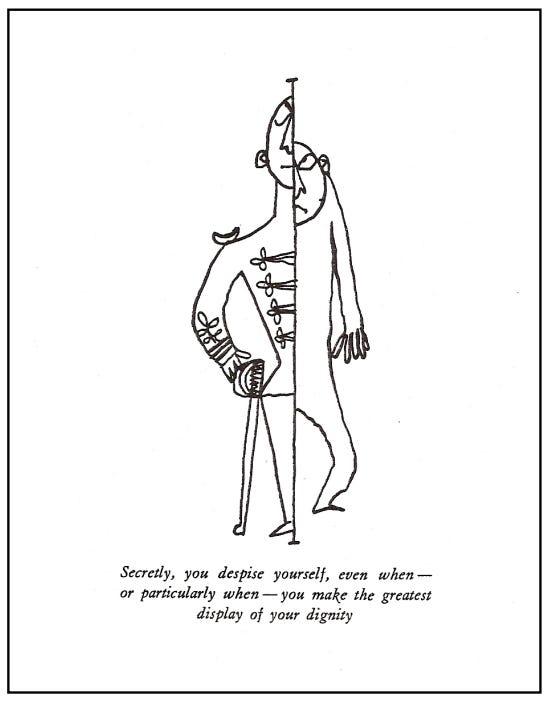

Telling the obscene truth about the little man should mean a frightening responsibility because of how often philosophers or scientists end up exiled or executed. Perpetually unconvinced, the little man seems to invite laughter, until such a pitiful object of ridicule turns out eerily familiar as an inner hatred of self.

“I tell you, little man, you’ve lost all feeling for the best that is in you. You’ve stifled it. And when you find something worthwhile in others, in your children, their wife, your husband, your father or mother, you kill it. Little man, you’re small and you want to stay small.” (23)

The little man has an unattainable ideal of the family or a race, rather than any concern for the community. The pseudo-community in a cult of personality is another neurotic symptom of the little man. When he is sick with a self-directed hatred, the little man elevates and defers to other little men. In comparison, one responsible expert seems worth all the hope and sympathy the masses of people lavish on an endless parade of snake-oil salesmen. The author, Reich, himself ended up convicted in the United States, and was imprisoned for peddling his own pseudo-scientific claims to have cured cancer with his own brand of sexual therapy. Despite his best intentions, the worst and lowest motives find a place in Reich too. He and the little man share the darkest drives as much as the desperately dwindling sources of love, forgiveness, and justice. These are, for Reich, the higher motives which ought to govern society as its truly sturdy supports, instead of its shamefully hidden indignities.