Embodiment in Christian-Mystic Meditation

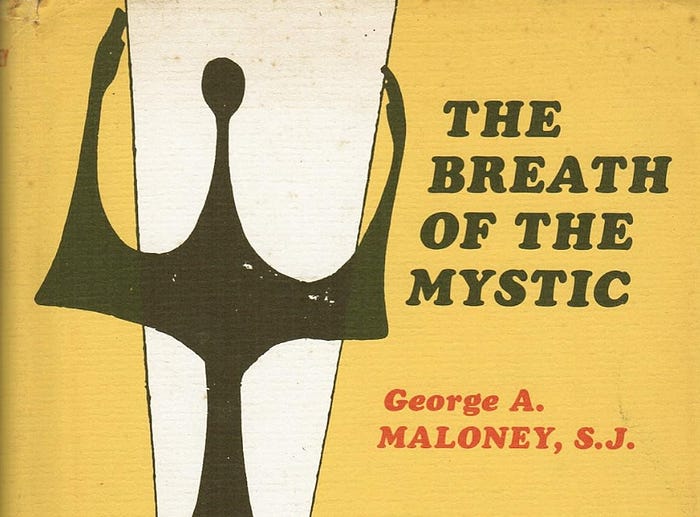

The Breath of the Mystic (1974) George A. Maloney, S.J.

Meditating has the outwardly impotent appearance of doing nothing, despite containing an energetic repetition. Concentrated on breathing and the body, George A. Maloney’s work, The Breath of the Mystic (1974) corrects mistaken impressions of meditation as a strictly mental practice. Common misconceptions overlook the intense embodiment which is entailed by meditating. Energized in a dialectical spirit, mystic critique holds modern social life responsible for neglecting embodiment.

“We live in the mind and disregard the body. We have forgotten the simple rhythm that God has planted within all of us: the rhythm of our breath […]” (Maloney, page 88)

Breathing and the body afford the rhythm which has a grounding effect. Without expecting any magic, meditating produces indirect results by provoking a practical inwardness. “Heaven is within” (Maloney, page 14) for the reason your own breath is enough, turning focus “within,” rather than elsewhere. Searching outwards for heaven leads to endless distractions. Accepting your thoughts as inevitably distracted, and repeatedly shifting focus onto the rhythm of breathing has a calming effect upon the body, which is ordinarily overwhelmed in our technological and competitive society.

“Our western mind is full of ideas, abstractions. We are always chattering noisily about an abstract world, while the real world recedes farther and farther from us. In all our activity, we are driven by a spirit of competition. We are conditioned to have a fixed self-image that remains intact even while we submit to constant pressures to be something in particular. Hence when we try to quiet the mind by concentrating on being one with the immediate world around us, we find ourselves besieged by thoughts and desires. Our true self is imprisoned by the false ego that is culturally hypnotized in the direction of endless conditional commandments. We have lost the wonderment of children who can enjoy simple reality with a curiosity and openness that allows them to be there, rather than wanting always to do something.” (Maloney, pages 85–86)

Under external pressures to perform symbolic and alienating social roles, to turn inwards means more than the merely introverted will to self-isolation. Spiritual life is not necessarily isolated from social life, nor entirely lonesome within silent contemplation. On its own, isolation is an insufficient condition for mystic experience. In his peculiar dialectic, Maloney deepens the meaning of solitude with a paradoxical inversion. “One enters a new world. Solitude is no longer solitude.” (55) Vita activa and vita contemplativa have their strict division abolished within the language of mystics. “The dichotomy between action and contemplation does not exist any more.” (56) Referring to Saint Gregory of Nyssa, mystic meditation frustrates further contradictions of “luminous darkness,” or the paradox of “sober inebriation” (76). Far from doing nothing, mystics have the advantage of finding stillness wherever, and with whomever.

Reaching what Maloney calls the “still point” in contemplation, Orthodox Christian mystics pray in “a basic rhythm of inhalation and exhalation” (pages 97–98). The simplest manner of mystic meditation is to silently repeat the four lines of the Jesus prayer: Lord, Jesus Christ (inhale), son of God (exhale), have mercy on me (inhale), a sinner (exhale). Of the Jesus prayer, the four lines sum up the doctrine of Christianity: the lordship of Christ, and petitioning for mercy from God.

Maloney credits a number of significant sources for mystic-Christian doctrine: “Origen, St. Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius, Meister Eckhart, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. John of the Cross” (54). Often ex-communicated for their unorthodox scholarship, Christian mystics endure difficult experiences without idealizing suffering for its own sake.

“These mystics were not neurotic people who took particular delight in suffering for love of God. They had entered into their deepest self where they began to lose the most precious possession that a human being has before he learns to surrender himself in love to the Other, the control of his own little world of reality. When you lose this, you either have to be insane or you are a mystic […]” (Maloney, pages 54–55)

Facing the multifarious demands of social life, mystic meditation risks insanity by surrendering self-control. The neurotic ambition for control, by constantly searching outwards, leads to perpetual distractions from the inwardness of spiritual life. In a sermon from the mystic Catholic friar of the Dominican Order, Meister Eckhart (circa 1260–1327):

“But anyone for whom God is not really within like this, who must always go and fetch him from outside, from this or that, seeking him in changing modes, perhaps in work or in places or people, that person is easily distracted, for […] he is hindered not merely by bad company but also good […] The hindrance is in him […]” (page 17 in Meister Eckhart, from whom God hid nothing. 1996 edition)

Whether in good or bad company, neither church nor state can abolish the inner hindrance to spiritual life. The only pathway upwards to spirit really passes below, by spiritualizing the body. Through the breath of the mystic, inwardness is the bridge to heaven, not vertically upwards, but horizontally inwards. “Heaven is within” (Maloney, 14) because you are near enough to heaven, and, crucially, separated from God by almost nothing.

“One does not have to run all over the whole world and to exhaust the gamut of human experiences in order to find God. In the beginning, contemplative souls need beautiful trees and flowers. As they become more and more advanced in contemplation, they follow the instruction of Evagrius, desert Father of the fourth century: “Go into your cell — go into your cell and don’t come out. It will teach you everything.” If you have God, you have everything, because you are touching the core of reality.” (Maloney, page 56)

The barren cell of Evagrius is empty without lacking anything. For this effect of abolishing the divide between having nothing and having everything, Maloney refers to a process he calls “kenosis, and emptying, in order that God may fill the void.” (25) One’s own self-will surrenders at the point when alienating identities lose their appeal as stylish self-reinventions. No self seems new enough to satisfy the desire for fullness. Within a process of emptying, the fullness of God is heard on the condition of silence.

“The Greeks looked upon their gods. But Moses heard the almighty, the transcendent […] God speaks in the quiet of our hearts and we hear him only when we silence the noise of our selfish desires […]” (Maloney, page 17).

Mystic critique silences the noise of established habit, rather than bolstering the culture of narrow individualism. Meditating provides no new identities, which are disappointingly commodified into expensive lifestyles, or selfish ideologies. Anyone who knows the burdens of debt can appreciate silent prayer as its own reward.

“Only when the contemplative enters into a vivid experience of his own utter poverty and sickness, of his incompleteness before his Maker, can he begin to experience something of God’s richness.” (Maloney, page 27)

As an essentially incomplete process, mystic meditation earns us a fleeting concept of God because “[…] as soon as we think we have understood His message, in that moment we have introduced noise.” (24) The noise of careless and unreflective habit is the inner hindrance to the ceaselessly changing dynamic of spiritual life. At the risk of seeming atheist, mystic experience consists in emptying oneself of one’s familiar concept of God. The mystic Catholic theologian, Meister Eckhart preaches:

“We ought not to have or let ourselves be satisfied with any thought of God. When the thought goes, our God goes with it.” (page 18 in Meister Eckhart, from whom God hid nothing. 1996 edition)

Mystic critique can only approach atheism by abandoning the shallow temptation to idolize a fixed idea of God. For the dialectical contrast to atheism, Maloney locates the light of spirit within the desert night which is darkest.

“If it were not so dark, if we had not lost our way and had not that feeling of utter alienation from God, we would have settled down to a secure possession of God. We would have said, “How good it is to pitch our tents here.” But it is dark and we have to be on our way, seeking the Lord. Thus God leads us further into the dark desert. As we descend more deeply within ourselves, God reveals our own abyss of nothingness before the Mountain […]” (Maloney, page 52)

Maloney’s emptying process aims at sacrificing all “secure possession,” even the safe attachment to a concept of God. A personal idea of God, which has become fixed, has lost what made it spiritual. Instead of seeking sound certainty in personal ideas of God, Maloney undermines the tempting attachment to religion which amounts to another ritual habit or fixed idea. Rather than a creed, Jesus taught his earliest followers the Lord’s prayer. Addressing God with the more familiar word for father, after Jesus prays, he warns against repeating empty words as an end in itself.

Without expecting any response from God, praying contains its own reward. The purpose of prayer is not so much uttering sweet nothings for their own sake, but the displacement of ordinary anguish, by the secret effect of repeating almost nothing.